AI and The Artist

It’s not replacing us. It’s exposing us.

What would your role in the post-apocalypse be?

I’m sure many of us have been on the receiving end of that question, or some variation of it. A nice little conversation starter, an ice-breaker.

When I was writing full-time, I hated this question.

When we imagine post-apocalypse scenarios—whether they be of the environmental, robot, zombie, or Biblical variety—we imagine ourselves stripped down to our barest essentials. Gone are our interests, opinions, and philosophies. We simply become a thing that does a thing. At our most raw, we’re forced to imagine what it is, exactly, that we do. What can we offer in a world that no longer needs us?

Unsurprisingly, this is a popular conversation starter for those in, or have been in, the military. In fact, I’d wager that being prepared for the apocalypse is not an insignificant reason that many people join the military. There are few things more heroic than maintaining order, offering protection, keeping people alive when the oceans rise and robots turn against their creators and zombies run amok.

Since a number of my family have served in the military, I’ve endured this role play a handful of times. When it came to my turn, people—who are well-meaning—were always quick to assign roles to me. Someone needs to document the history, they’d say. Someone needs to write the story of the post-apocalypse.

Being a writer—or any creative, for that matter—is a constant battle, both internal and external, to prove your worth. But let me tell you: nobody’s going to need a fucking bard in the post-apocalypse. When humanity is stripped to its essentials, we offer... what? Our skills are ornamental, decorative.

Which, I think, explains The Artist’s underlying fear of AI.

It’s not just replacing us. It’s exposing us.

****

I’m a teacher now, which I guess adds a little more worth to my post-apocalyptic prospects. If I find myself in charge of leading 30 or so teens through a decimated wasteland, for example, I could do that (I mean, in theory. In reality, I’d rather put my neck in the snapping jaws of a zombie).

As a teacher, it should be no surprise that I encounter AI a lot. And in high school, it’s very easy to spot. A kid who is unable to summarize basic plot elements of a story will suddenly turn in something with words like diegesis and fluctuation and encapsulation. At this stage in their apathy, they’ve just learned of ChatGPT’s awful power, but not yet honed it. I feel for every professor in higher education who has to navigate these robot-generated essays whose prompts are so locked-in and precisely deceptive that we can only lament mental effort used to draft them instead of actual thinking.

Recently, I asked a well-respected writer friend—who’s also a college writing professor—how he uses AI in the classroom.

“I don’t. And I actually think less of people who do,” he said.

Which, fair enough. It’s the duty of The Artist to stake a claim, and being anti-AI is one of the least dumb hills to die on.

I think my response, though, was: oof. Because I use AI a lot.

****

Here are some of the ways that I use AI:

· ChatGPT is very good at translation. I have over four languages spoken in each of my classes, with a large population that speaks Haitian Creole. Haitian Creole is a tough language to translate because it’s not really a written language. The people who get education in Haiti learn to write and speak in French. For this reason, there are fewer sources of Haitian Creole on the internet (at least compared to other languages) that translating bots can pull from. Before, I’d Google Translate materials, and often get strange looks from confused kids. ChatGPT, for whatever reason, is really good at translating Haitian Creole.

· I write my own vocabulary tests, but I will always use ChatGPT to make at least four variations of them—similarly worded questions, scrambled choices, different fill-in-the-blanks. It’s a really easy way to cut down on students copying each other (although, some still find a way to cheat, which actually instills a bit of awe in me. The resourcefulness of teens.)

· I often create scripts for kids to read aloud in order to practice speaking. I ask ChatGPT to give me three levels of difficulty, based on word complexity, vocabulary, length.

(How much water am I using to do this? How deep am I sending the Earth into environmental collapse to meet the needs of immigrant youth? Who knows. Probably less than an influencer. Probably less than a person who’s daily Instagram stories look like - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -. )

- I will create a project, put the description into ChatGPT, and ask it to tell me how I can scaffold it for low, medium and high-level learners.

- I will use Gamma to create a slidedeck for specific instructional necessities. For example, when I was having issues with students using phones during class, I had Gamma create an image-heavy slideshow illustrating the drastically negative effects on mental health from phone use over the past 15 years. Not that it really resonated with kids, but at least I had something I could fall back on when I took their phones away.

The list goes on, but I hope it’s clear that AI has been a boon for accessibility and equity in education. There are days when I have to do all the above in a single 90-minute prep period, and to do so without AI would take days, weeks. AI allows me to eke out time and mental stamina to do so. Although I love teaching, I still love to write. In fact, I need to write. For The Artist, it’s not a choice.

Otherwise, just bring on the tidal waves.

****

Defenders of generative AI “art” will tout its accessibility. Okay. But does being a breathing person entitle me to all the skills that humans have developed and honed for thousands of years?

Accessibility, I believe, does not apply to art. Art without exclusivity is not art. When everyone can art, then there is no art; there are only products.

What’s distressing is how well AI is at masking itself as art. This is what The Artist fears. This is the underlying impetus that fuels The Artist’s overarching hatred. We see the number of Spotify streams garnered by AI artists, the popularity of AI actress Tilly Norwood, the best-selling AI-written book “Tech-Splaining for Dummies”, and we panic.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that AI “art” has been so widely accepted and consumed by the populace. People have been writing and consuming shitty books since the beginning of art. Listen to any alt-rock hit from the mid-to-late ‘90s and wonder: how is this not AI? Although I haven’t seen any clips of Tilly Norwood, I can’t imagine that Tom Cruise has any more personality than her.

Which is to say that the banality and predictability of popular culture is the culture we’ve rewarded with our money and attention. The human mind, generally, craves familiarity, so it’s not very difficult for a robot to emulate it. And now, with the ubiquity of handheld distractions, even the most simplified and saccharine formulas pass without much interrogation. The people who can’t tell the difference between art created by humans and machines, I imagine, are the same people who listen to algorithm-created playlists and watch movies with a phone in one hand. They are passive consumers of art, or what they believe to be art, which makes it pretty easy for a robot to slip one past ‘em.

Before AI, though, The Artist could at least take secret, smug satisfaction in knowing their hard work, perseverance, and talent is somehow better than what’s popular. Every Artist, I think, harbors a deep, virtuous sense that what they do is profound and indelible. But on a deeper level, they do it because otherwise they’d die. It’s very easy to tell the difference between a piece of art that was created with an invisible gun to the head, and one that was created for the prospect of earning money. And for better or worse, one of the appeals of creating art is comparing it to work by people you don’t like. All art should be, at least in some small way, an act of revenge.

But when imitation AI “art” becomes popular, the realization is: it’s not that people make bad art or the population has bad taste. It’s just that nobody cares.

What The Artist does will never be essential, and that’s how AI is exposing us. In the post-apocalypse, we’re learning that our books, our music, our performances, our ideas would be better put to use as kindling.

****

Most of us have seen Terminator. We’ve imagined what a world would look like if robots became self-aware. In the most grim post-apocalyptic scenarios, we were given a task. Even if it was a pitiable task like recording history, at least there was some agency and validation in that. But now, as robots actually are taking over, it’s looking like we won’t even have that.

****

A few upcoming events

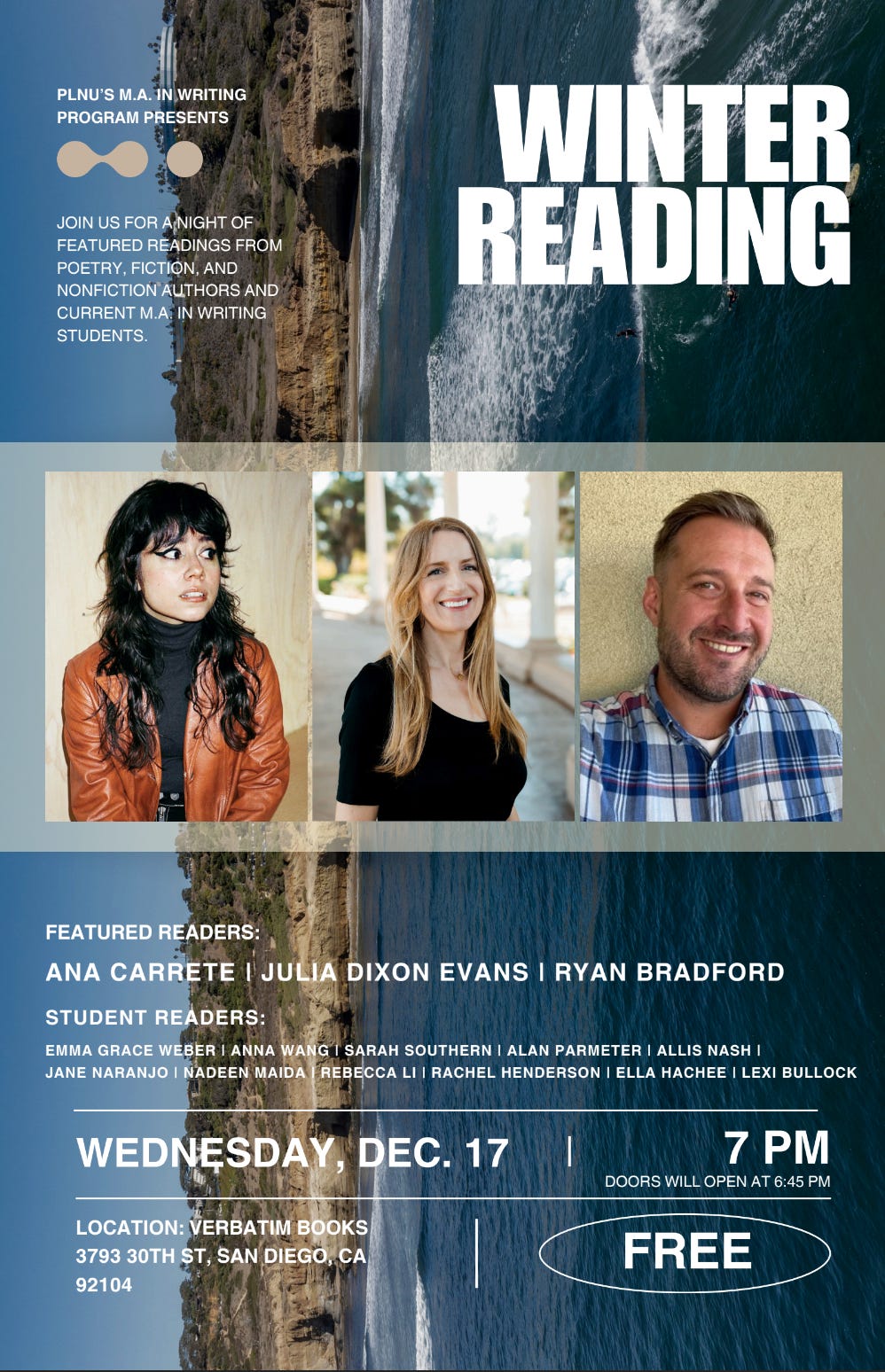

I’m very excited to be part of PLNU’s Winter Reading event on Wednesday, December 17, 7:00 p.m. at Verbatim. [Staind voice] It’s been awhile [/Staind voice] since I’ve done any literary event, and this one will be a winner. I’ll be reading from the Later Fees Blockbuster zine I put together a few months ago, and I’ll have a few copies for sale. If you didn’t get one in its original run, now’s your chance.

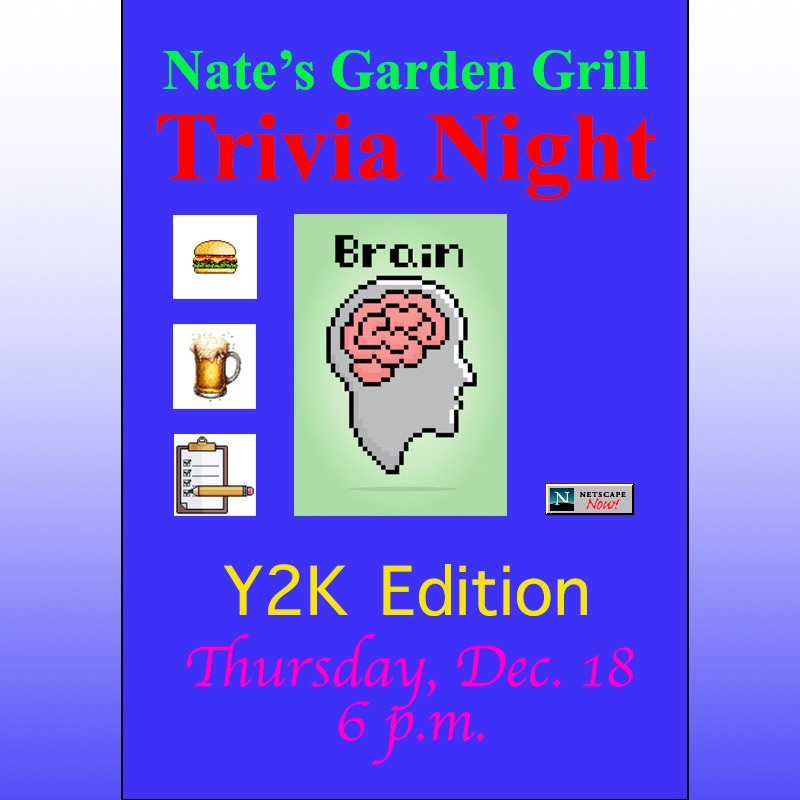

The next night (Thursday, December 18) I’m hosting the last trivia of the year at Nate’s Garden Grill. I’ve been doing trivia for about two years now, and I still find much of joy in it. I love to watch how teams work together and facilitate a space where reliance on Google and tech is not only shunned, but shamed. Anyway, this edition is called the Y2K edition because I didn’t want to write a bunch of Christmas-themed questions. Gen Z is gonna love it.

long live the JDE/RB dream team. also, great post

Fascinating. How much of our perceived 'worth' is just societal construct, and isn't the act of creation inherently valuable, you briliant mind?