Understanding your anxiety through horror films

Taking comfort in frightening flicks when your head is a house and the calls are coming from inside the house

A scene from John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978)

Laurie Holden sits in the back of a classroom. Given her prudish, overachieving personality, her placement within this educational environment seems unlike her. The camera slowly zooms up the rows of desks populated by her high school classmates, all defocused in the peripheral, and we understand her placement in the frame: she is a target. Apart from and a part of her environment.

Laurie looks out the window and sees a brown station wagon parked across the street. Behind it stands the ghostly figure of Michael Myers. She doesn’t know it’s Michael Myers — it’s just a shape. In fact, that’s how the character is credited — not Michael Myers but “The Shape.” An unstoppable, amorphous force of evil.

The teacher calls on Laurie to answer a question. Laurie answers. When she looks back out the window, both the car and The Shape are gone.

It’s October 2013 when I first notice that my heart is racing. There’s been a slight discomfort there or as long as I can remember, but now it’s cranked up to Spinal Tap levels. I place a hand against my chest and feel the heavy thumping of that knotty muscle. An ample pressure has been rising in my chest for the past few months. I’m scared that it’s going to blow. I look around at my co-workers and try to decide on whom I want to aim my chest toward when the sucker erupts. Who do I spray?

My boss talks to me. He looms over my desk like he’s 20 feet tall. I don’t know what he’s saying, but I grit my teeth and nod. How can he not hear my heart? I like him, but at that moment, he’s a threat. This feeling is fight or flight. My place of employment has become a terrifying environment, just like Laurie’s classroom.

My surroundings have become terrifying. I feel like a target in everyday life. It’s a feeling that’s always been with me, but now it hits a fever pitch. The Shape has come for me, but a mask-wielding character does not personify it—just illogical, amorphous forces that cause fight-or-flight physical reactions.

I sit at my desk and quietly wait for the panic attack to go away.

A scene from Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead (1981)

Evil has possessed Shelly. She lumbers toward her former friends, Ash and Scott, milky-eyed and reaching to claw the life out of them. Ash holds an axe, but he cannot bring himself to strike Shelly. Scott screams out “Hit her! HIT HER!...HIT IT!” Scott grabs the axe out of Ash’s hands and savagely dismembers Shelly until blood pours down the screen.

Afterwards, Ash and Scott step back and watch Shelly’s body parts shiver in puddles of blood. They can’t even look in each other’s eyes. Ash asks, “What are we gonna do?”

Scott says, “We’re going to bury her.”

“We can’t bury Shelly,” Ash says. “She—she’s a friend of ours.”

For Ash, Shelly is still their friend, not the monster laying in pieces at their feet. He doesn’t yet know that things will never be normal again.

In 2013, I become despondent. The stress of work, health, family, life — everything a healthy person should be able to balance — becomes too much.

I decide to see a psychologist. It feels like admitting defeat after trying so hard to fit into normal society. This is the hell of mental illness: doing everything right and still feeling wrong. I long to maintain normalcy, even if it feels like my nerves and psyche are being chopped apart like a deadite in the woods.

I see the psychologist three times. He’s a very nice British man which puts me on guard in fear of offending him. But when he asks what my interests are, I say horror and “dark stuff.” He lifts an eyebrow and writes something on his notepad. I only see the psychologist two more times.

A scene from David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986)

Scientist Seth Brundle has fused himself with a fly. It’s a slow and monstrous physical transformation. “The disease has just revealed its purpose,” he says. “It wants to turn me into something else. That’s not too terrible is it? Most people would give anything to be something else.”

I tell my doctor my symptoms, and she prescribes 300 mg of bupropion. During that first week, I feel alert, happy, carefree. I lose a little weight. It’s amazing.

After some time, however, I notice my jaw clenching. I sweat like a madman. A twitch appears in my right eyelid. Certain songs and commercials make me cry. I don’t feel in control of my feelings anymore. These are the transformations that are turning me into something else.

A scene from John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982)

MacCready sits alone in an office, drinking J&B scotch. An alien with the ability to take on human and animal form has infiltrated his Antarctic research station and a raging blizzard has isolated them from the rest of the world. The scene is lit blue, accentuating the bleakness. He speaks into a tape recorder: “Nobody... nobody trusts anybody now, and we’re all very tired.” He stops the recording, rewinds and plays it again.

I watch horror movies in October 2013, the year I’m diagnosed with anxiety. I’ve watched them every year leading up, and will do every year following. It’s one of the few occasions where my anxiety feels natural. Horror has been a method by which I can understand my own illness, and an anchor that’s kept me tethered amidst all the fear of the real world. Anxiety is tiresome and it often makes you feel very lonely, but it can be comfortable in the darkness among all the skeletons and monsters and ghouls. Sometimes the darkness can feel like a hug.

SICK FLICKS

Over at PACIFIC Magazine, I wrote about the best horror films featuring diseases, because everyone keeps talking about viruses for some reason. Check it out.

THE WEEKLY GOODS

Adrienne Barbeau exemplifying the benefits of horror radio in John Carpenter’s The Fog

Listen to this

This past decade has been a golden age for horror films, with talents like Jordan Peele, Jennifer Kent and Ari Aster lifting the genre in order to tell deeply affecting and personal stories. Not to sound all hoity-toity — because I like a stupid, dumb slasher as much as the next horror bro (brorror) — but the genre has much more potential than gore and jump scares. And that’s what I set out to do when I created the literary horror journal, Black Candies to provide a platform for smart horror that reflected the anxieties of our times. This October, SSWA, in partnership with La Jolla Playhouse, has produced a handful of stories from the different Black Candies volumes (some of which were co-produced and edited by Julia Dixon Evans and Natanya Ann Pulley) as radio plays called Listen With The Lights Off. The stories are professionally acted, with styles that range from horror-comedy (Jay Wertzler’s “Welcome Back”) to heartbreaking (Juliet Escoria’s “This Is A Ghost Story”). Make sure to listen to the past episodes on whatever platform you use to listen to podcasts (just search “La Jolla Playhouse Presents”). All hail horror.

Read this

As mentioned above, smart horror stories have the power to burrow their way deep into our souls and make us rethink the world around us. But for those looking for more visceral scares — you know, the tingly goosebump kind — check out Jezebel’s annual reader-submitted horror shorts. Every year, the popular site allows readers to share their “true” horror stories in the comments, and then Jezebel publishes the best ones. Like all good creepypasta (i.e. internet urban legends), these are frightening because they’re so random, half-realized, and ethereal. Horror doesn’t always require logic, plot or narrative and, in fact, it more often benefits from a sense of unreality. I got legit shivers while reading the story by user kinbari about the wind sounds.

Read this

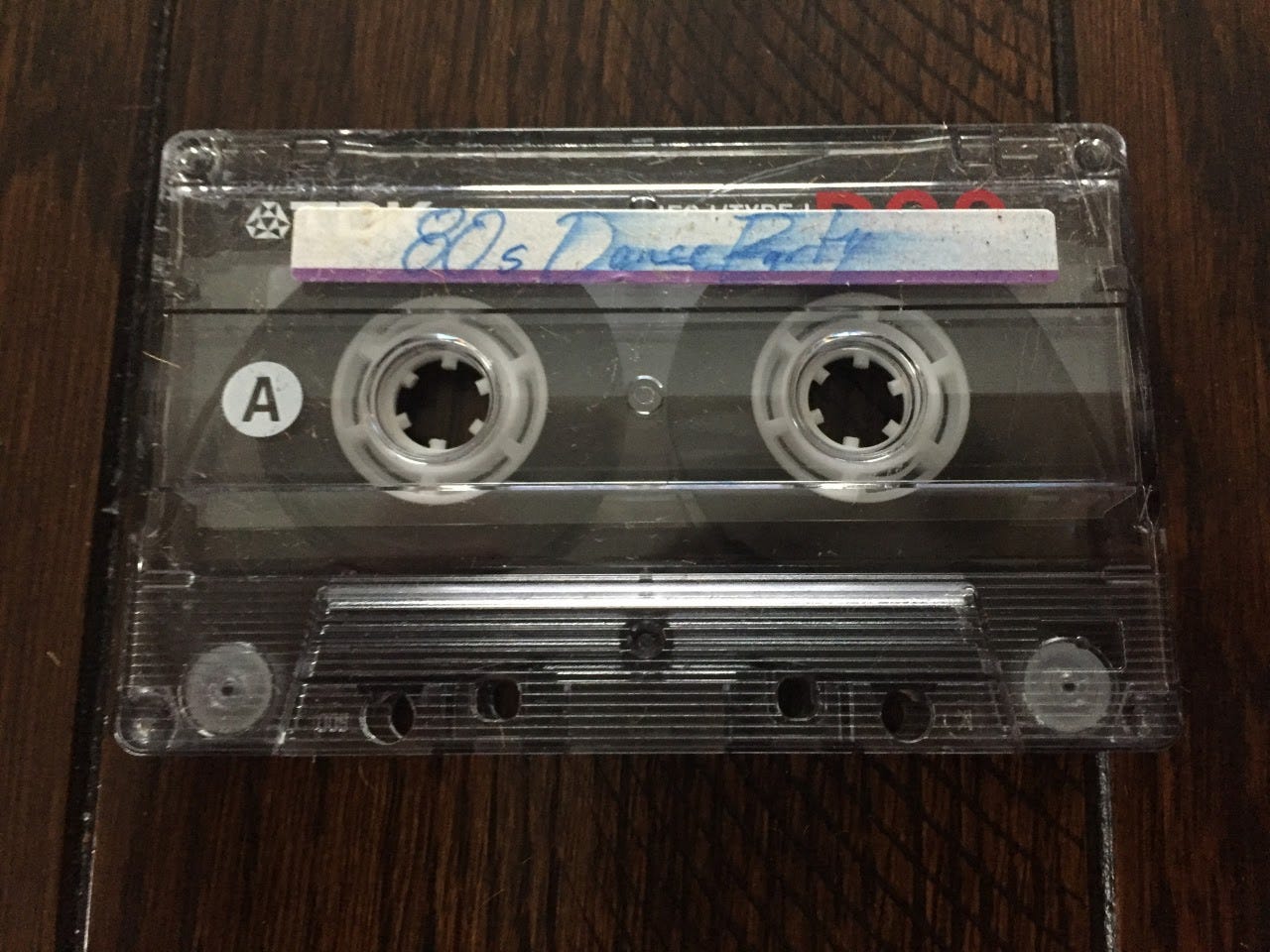

Did I ever tell you about the one time I found a haunted cassette tape?

Happy Halloween, everybody! Hopefully democracy is still a thing when we speak again.

Got a tip or wanna say hi? Email me at ryancraigbradford@gmail.com, or follow me on Twitter @theryanbradford. And if you like what you’ve just read, please hit that little heart icon at the end of the post.

Julia Dixon Evans edited this post. Thanks, Julia. Go follow her on Twitter.

How did you find out about the listening party?