“Have you cried yet?”

It’s one of the first questions the teacher support specialist asks. We’re sitting in my empty classroom at the end of the day, during my prep period. She sits at a student desk while I hurriedly tidy up from the previous period. I sweep up broken colored pencils, crumpled pieces of paper, little piles of crushed Takis. There are always Takis.

What counts as crying? Does it count to lock yourself in your room after a difficult class, turn off the lights, and silently shed a few tears? Like, how many tears does it take to count as crying?

At the suggestion from colleagues, I reached out to the teacher support program for help. The program is meant to provide support for ineffective or troublesome teachers, but I’ve been told that if you self-elect into it, it looks good for you. Shows your eagerness to improve.

It’s not so much that I want to improve—I need a base to start from to do that. I want to know where to start. If there was a theme for my first year as a public school teacher, it would be: Fuckfuckfuck!

So have I cried yet? I force myself to laugh at her question. “No,” I say. She knows it’s bullshit, but she’s nice enough to ignore it.

*

Near the end of October 2022, I land a job teaching ESL (now known as ELD—English Language Development) to 9th and 10th graders. The students have already spent eight weeks with a long-term substitute, so my arrival is a little like jumping into chummed-up water. I’m a new face, yet to be trusted. Some of these students have traumatic stories: fleeing natural disasters and/or violence. Some have crossed literal deserts. Understandable that they’d have trust issues. My arrival sparks a current of worried looks.

The first few weeks go swimmingly. The students are eager to learn. They’re polite. They give me fist-bumps.

Then, three weeks in, a student—through an electronic pocket translator—tells me to fuck off.

I’m trying to help him with his math, and he’s been talking to his friends during the teacher’s lesson, so when it comes time to do the assignment, he does not understand. Using the translator, I make a quip about how maybe he should’ve been paying attention. It must translate into something barbed, because the student’s friends laugh when I show the screen. The student requests the translator, says something into it, and hands it back.

“Why don’t you go fuck off?” it reads.

I stare at the words, unsure of how to handle this situation. I imagine sending him to the office, where he can sweat it out under a thousand hours of boring minutia. Perhaps I could take away his soccer ball. Or I’d redesign my seating chart so he’d have to sit front and center, where I’d call on him relentlessly.

I then think of the advice my friend and colleague told me soon after I got the job: new teachers have a tendency to go overboard with their discipline, doling it out like a baby rattlesnake unable to control its venom.

Don’t be a baby rattlesnake, don’t be a baby rattlesnake. It’s a mantra I’m trying to drill into my brain.

I tell the student that his language is disrespectful and I could send him to the office. He looks shocked.

At the break, he returns with a counselor who speaks Spanish, and she explains that the student is afraid he offended me. The counselor explains that the student thought we were just riffing, joking around, but something in the translation process got messed up.

The student sticks his hand out. We shake, and I’m thankful I kept the venom in.

*

Every day is like a play performance that I’m only 60% prepared for. My lines are half memorized, I’m missing props, I only have a gist of what the play is even about. There’s no wardrobe department, so sweat seeps through my armpits and my skin is perpetually breaking out. I imagine drama nerds have had this nightmare once in a while, but this is every day.

But there is this transitory sort of magic that can happen under these circumstances, a sort of synergy that manifests when the students are engaged, their eyes on you, and they’re hanging onto your words like the crew of a ship. On good teaching days, there’s a certain rhythm that couldn’t be repeated even if you did the exact same lesson the next day. Not to belabor the extended dramaturgical metaphor, but performances live or die each night, even if you’ve memorized the lines.

Here’s another thing nobody told me about being a teacher: kids, for the most part, will do what you tell them. This power is intoxicating—I feel it surge through my veins! I don’t mean that teachers should be authoritative (although some teachers [bad teachers] are) but the potential for collaboration is amazing. It’s rare in life that you can be like, “Let’s try this,” and 20 individuals will respond, “Okay!”

*

Kids don’t really like movie days anymore.

It’s the last day before Halloween and I’m practically shaking with excitement at the first opportunity to bestow the gift of movie day.

As I fire up Netflix, a handwritten scrawl appears in my head: Dear students, here’s the movie day you’ve all been waiting for. Signed, your cool teacher.

I play Nightmare Before Christmas, and then sit in one of the desks, modeling the excitement and eagerness with which I expect. But I turn around and see that all of them are either talking or sleeping.

Now, if I want to give students a treat, a special day, I let them use their phones. Phone Days are the new Movie Days. But do I ever give them phone days? No.

Except on Valentine’s Day. Really, it’s my fault for trying to teach anything on the most hormonally-charged day of the year. I’m showing a slideshow, but can’t even hear the words coming out of my mouth. Kids roam from desk to desk, handing out candy and smelling each other’s rose bouquets (where did so many bouquets come from??). Even kids from the class across the hall are in my room for some reason. I finally say, “You guys don’t care. Come get your phones.” I stew at my desk for the last 30 minutes of class. One student asks me “What are we doing?” I say, “I don’t know.”

*

(However, on the day before winter break, I put on Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio, and again, very few students are watching, except for one lone student in the back. In the movie, Pinnocchio dies multiple times, and at one death, the student in the back yells “NOOO, PINOCHO!” (the Spanish pronunciation of Pinocchio) and it instantly becomes one of my all-time favorite memories.)

*

On some days, a class period can feel like one of those dreams where you have a goal or destination that becomes increasingly impossible.

Here’s how it could go.

Class starts.

Five minutes in, only about half the class are in their seats. Do I start without the stragglers or move ahead and risk having a handful of students lost.

10 minutes in, and everyone’s in their seat. I weigh the benefits of addressing the tardies, and decide to table it for later. Every day is an ongoing series of what battles I want to pick.

Take roll, do a warm-up exercise, and then intro the lesson. “Today we’re going to learn about this common verb.”

I ask kids to take out their computers. Four of the kids don’t have their computers. Another handful have lost their login information. There may be a new kid who doesn’t yet have a computer. Take the next 10-15 minutes trying to solve all these tech issues. Meanwhile, students start asking to use the bathroom. Two kids ask if they can go together, and I say “one at a time.” They’ll sit down, wait a minute, and then the first one will ask again; the second student will follow shortly behind, needing a pass to the nurse’s office.

I’m 30-40 minutes in and haven’t even really hit any substantial part of my lesson.

Start the lesson, and then the phone rings. It’s the health center, requesting to see a student for a medical issue.

Start the lesson again. For 10-15 minutes, the kids are paying attention. Yay.

Set the students on their task. Cycle through the class to check on the work. Most kids are focused, but the ones who are not are very bad at hiding it. Kids are terrible at being inconspicuous, like deer in headlights.

The counselor shows up at my door with a new student at her side. Bring the new student in, make them feel welcome, try to carve out a few minutes to introduce yourself and get to know some basic information. Another student interrupts, needing to go to the bathroom. Have the other students returned from the bathroom yet? Do I really care?

A student on the other side of the room begins sobbing. Turns out their romantic interest just broke up with them over Instagram chat, which they weren’t supposed to be using.

Spend 5-10 minutes consoling them.

The bell rings. The students who did the work want you to check it, but it’s the off-task kids whose work that I really want to see, and they’re already gone, snuck out.

Everyone leaves, and I’m alone, thinking “What did I accomplish today?”

Every day, you’re an educator, a social worker, a technology troubleshooter, a diplomat, a mediator, a bargainer, a coach, and it sometimes feels like a miracle if you get any instruction in.

*

Every teacher tells me that you need at least five years in the classroom to really know what you’re doing. In fact, I recently read an older interview with Frank McCourt, educator and Pulitzer Prize winning author of Angela’s Ashes, who said that it took 11 years for him to feel comfortable in front of students.

On one hand, it’s dispiriting to imagine how long I have to keep at it to be competent at my job. I feel it constantly, like a little black cloud of self-consciousness that materializes whenever I’m in a room with other educators. I feel it whenever I talk about strategies or activities I’ve attempted, eliciting looks like, “Aw, cute.”

But on the other hand, I have lots of leeway to do whatever. One of my favorite things I’ve discovered is doing karaoke with the students, assigning a new song each month. I try to find songs with lots of repetition and some good vocabulary, and the students get three or so weeks to practice. I’m not sure what the pedagogical value is to this—maybe some sort of gamification of reading?—but I’ll try anything to get the students to speak out loud.

On karaoke day, I sit next to each student and give them a choice of regular speed, a slowed-down version of the song, or just reading the lyrics off a sheet of paper. Singing isn’t required, I just want them to read along the highlighted words. But some kids do sing, and there are few things better than listening to a nervous English learner quietly singing Kelly Clarkson next to you.

*

Each day has a different vibe. Mondays are good for reviewing old material because everyone’s kind of tired and their brains are resistant to absorbing new information.

Tuesdays are low-key the best. There’s no excitement for the weekend yet, so students settle into the idea that they might learn something. I like to try new strategies and activities on Tuesdays—the kind of stuff that intimidates me the most. Most of the time it doesn’t work, but sometimes it does and, voila, I have another new tool.

Wednesdays are short days, which were great when we were students, but as a teacher, the modified schedule just throws off the whole rhythm of the day. I never get used to it. Not really a fan of Wednesdays.

Student energy is always the strangest on Thursdays. I don’t know what happens to teens on Thursdays, but they’re the most irritable and disagreeable. Bad attitudes abound. During student teaching, my guide teacher said that I need to take a day off, make it a Thursday. Thursdays are good days to give tests or quizzes.

Fridays are fun. Students are in a good mood; I’m in a good mood. The weekend hangs over everything, but that excitement can motivate students to do their work. And even if students are off task, what do I care?

“Fri-yay,” I think, staring dead-eyed out the window.

*

A few months in, I’m talking with a colleague, who genuinely asks how everything is going. I say it’s fine, it’s challenging, but I like it. She asks if I’ve cried yet. Everyone seems to ask that.

We start talking about our personal philosophies of teaching, the “why” of what we do. She’s been an educator for two decades, and believes that therapy should be a prerequisite for all teachers. She says too many teachers get into it to fill some void in their own life. These are the ones who constantly post notes from their students on social media—notes that say “you’re my favorite teacher” or similar sentiments. These are the teachers who see themselves in Dead Poets Society.

Teachers are always the heroes in their own minds. But the teacher is never the hero. We are authority, we have to enforce rules, we have to maintain order. We’re buzzkills, stoppers of fun, enthusiasts for making nervous teens speak in front of the class. And once I realized that, teaching became slightly easier for me. Everyone likes being liked, but absolving my inclination to be a Cool Teacher has allowed me to work toward being a more authentic person—which, ultimately, teens respect more.

But it’s not easy. There’s a lot of pushing through difficult emotions. It’s almost like internal excavation, pushing aside all the layers of self-deprecation and my Golden Retriever-like need to please everyone.

When my colleague tells me—somewhat astonished—how chill I am with the constant spiritual and emotional bulldozing that teachers endure, I respond: “Please. I was a journalist for 10 years. This is nothing.”

*

Afternoon meetings are the worst. It seems like I’m the only person whose belly makes horrible, disgusting noises after I eat. It also doesn’t help that there’s a Wienerschnitzel pretty much on campus, and, god help me, I’ve grown a fondness for their chili cheeseburgers.

In a quiet room, with about 10 colleagues, I know it’s going to happen. I feel the food shifting in my gut. I move in my seat, try to make as much auxiliary noise as I can—maybe that’ll mask any potential gurgling. But right when there’s a pause in the discussion, my stomach decides to do me an unkindness. It sounds like the death rattle of my insides. It’s so loud that whoever was about to talk pauses, their mouth hanging open. Everyone in the room stares at me.

Unable to think of anything clever, I do the gag where you’re as confused as everyone else. I slowly turn around in my seat, checking to see who behind me could’ve made such a gross sound, but there’s nobody behind me.

No one thinks it’s funny. In fact, they all just look concerned. “I’m sorry,” I say. “Carry on.” I want to apologize not just for the sound, but for who I am and who I always will be.

At the end of the meeting, when we’re going around the table to see if anything has anything they’d like to add, I say “I think you’ve all heard enough from me today,” which gets a little bit of a laugh, but then one colleague looks at me and says with a mix of sympathy and pity, “We’re all human.”

Anyway, that story’s not about teaching. Just a reminder that the profession hasn’t completely changed me.

*

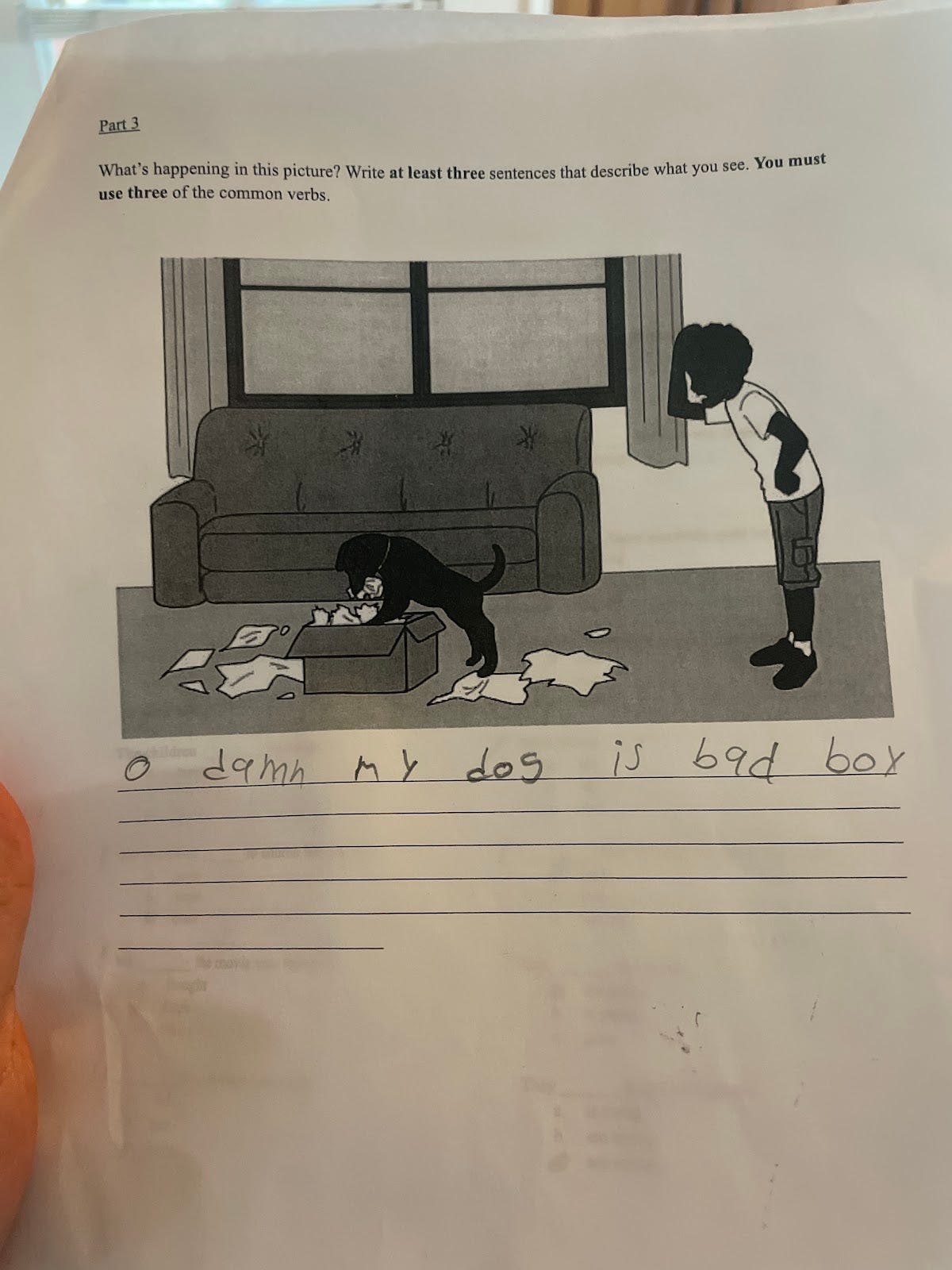

Near the end of the school year, our department takes all the ELD students on a field trip to the San Diego Safari Park.

On paper, keeping track of the welfare and safety of over 100 teenaged English learners seems like a nightmare, but field trips are incredible opportunities to watch how students act in the real world. Students keep track of each other, even if they don’t regularly socialize or get along in the classroom. “Where’s so-and-so?” they’ll ask if a person in the group goes missing. Some even let their crushes emerge on field trips. They buy each other food. They show their compassion.

When we stop for lunch, a girl hands over a sack lunch that she packed for me. Inside, it’s a variety of chips, candy, and sweets—probably less healthy than anything I could buy at the zoo, but I’m overwhelmed by the kindness of the gesture. And it’s at that moment when I kind of want to cry.

DONATE TO THIS

Trash Lamb Gallery is a gem, an inimitable addition to South Park and San Diego as a whole. The eccentric gallery/gift shop opened up in October 2020, which, as we all remember, was mayyybe a difficult time to be a new business. But the artist-owned space managed to survive through the worst of the pandemic, and has put on some killer art shows since (including one by the late/great Rick Froberg). I’ve made it my destination shopping spot every December, because I know I’ll find twisted or thought-provoking gifts for the weirdos in my life. Now, Trash Lamb is struggling, and they need our help. If you have the means, please throw some money toward their Gofundme.

GO TO THIS

I’m hosting trivia again at Nate’s Garden Grill this Thursday, Aug 17 at 6:00 p.m. sharp. It’s the last trivia of the summer, which doesn’t really mean anything, because I’ll be back next month, but you should just come, okay??

Get your teams together, take your neuro pill brain supplements or waterver, and come on down. Get there early to secure a table.

Got a tip or wanna say hi? Email me at ryancraigbradford@gmail.com, or follow me on Twitter @theryanbradford. And if you like what you’ve just read, please hit that little heart icon at the end of the post.

The stomach bit is laugh out loud funny.

Whenever your newsletter comes out, Jake and I just text all our favorite parts back and forth. We both were bulldozed by “Every day, you’re an educator, a social worker, a technology troubleshooter, a diplomat, a mediator, a bargainer, a coach, and it sometimes feels like a miracle if you get any instruction in." And we both laughed a lot at the stomach bit. omg.

Thanks for writing something as profound as it is funny!