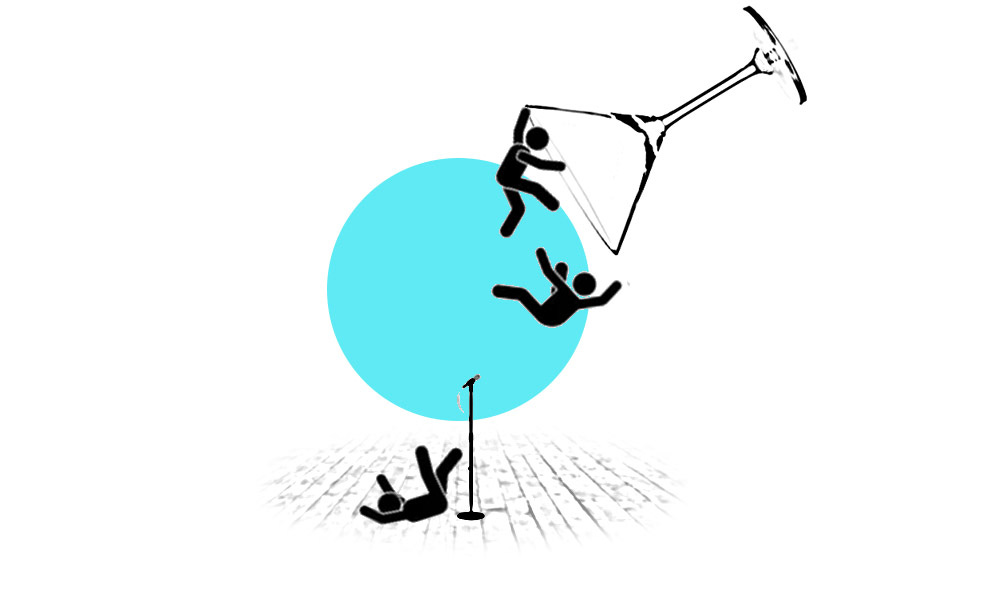

Keep Dry, Stay Clean, Hit the Stage. Now Do It Again.

Guest contributor Ombretta Di Dio explores the challenges of being a sober performer

Brooke Gerbers, 27, talks about their hometown of Woodburn, Indiana like the place is straight out of an E. E. Cummings poem. Three cornfields surrounded Brooke’s high school, where they played volleyball, basketball and ran track. Sundays were for church, Brooke says, and time spent outside of it was often shared with their grandma, who lived right next door. Parents in this small town (pop. 1,567 as of 2021) didn’t have to worry about whether kids would make it home safe after riding their bikes all day.

Things got a bit complicated when Brooke came out as queer in high school—something their family didn’t immediately accept. Things got even harder when Brooke left town for college. They didn’t venture far—less than 20 miles away from home—but that’s when their issues with alcohol and coke began.

In college, Brooke found a community. They started working in the bar industry. They played basketball and went to class. They had a life. Loneliness wasn’t exactly the problem; neither was boredom.

“I was drinking and using drugs because it didn’t feel like I had a purpose,” Brooke says.

The issues got progressively worse, so much so that in February 2018, Brooke spent four days awake at their drug dealer’s house, not a word to their friends about their whereabouts.

This was their wake-up call.

I can’t make it past today, Brooke thought while lying awake in a confused state of desperation. I am either going to kill myself or go to rehab.

Dr. Dan Gordon, a psychiatrist who specializes in addiction, explains to me that it’s not so much the rock bottom that pushes people to get sober, but the so-called wake-up call that follows it. That is to say: rock bottoms know no rock bottoms.

“Many people told me they have had five or six different bottoms,” Dr. Gordon says. “What people need is a wake-up call.”

And what that wake-up call looks like is different for everybody.

“It can be your boss telling you that you are suspended from your job, or getting arrested for a DUI,” he continues. “But at the time of the wake-up call, you need to get into recovery or there will be another bottom.”

In Brooke’s case, there wasn’t. With a backpack full of books, a toothbrush and nine different substances in their body, Brooke got themselves admitted into rehab. After getting clean, they traded drugs for the pen and became a poet. Leaving Indiana far behind, they landed in San Diego, where they found new happiness in performing slam poetry—their rhymes quickly becoming an online sensation, eventually finding a permanent home in printed publications. They began performing regularly, packing bigger and bigger rooms in and out of state.

“In the Midwest, we were taught to brush things under the rug,” Brooke says of their first performance at Queen Bee’s in North Park. “So, I took all those things I wasn’t allowed to talk about and said them out loud in front of 200 people. It was like an exhale.”

Now approaching five years of sobriety, and headed to Seattle for their next adventure, Brooke doesn’t really miss the booze. In fact, they don’t even get tempted at events.

“When I have that feeling [of temptation], I tap out for the night.”

Through art, Brooke has found purpose, they say, so much so that sobriety is now part of their identity.

Purpose resonates just as loudly in the words of standup comedian Kane Holloway, 36.

I met Kane at a comedy show somewhere in Chula Vista in the middle of 2022. The crowd wasn’t hot that night, but unlike me, Kane was able to keep those absent folks entertained throughout. From the handful of booze-free months I had under my belt, the almost six years he was mentioning in his act sounded like an eternity. Kane made it to San Diego in March 2022 by way of Los Angeles, from Seattle. He was driven by the desire to be happy, he says, and he hadn’t found any happiness in LA.

Despite growing up shy, he loved being the center of attention and, deep down, always knew he wanted to be a comedian. He has now been one for 14 years.

“As a kid, I saw Brian Regan on Comedy Central, and, one day, I did his act for my mom,” he says. “I said I created the act, which made me realize I could get admiration for my own material.”

Today, Kane uses his comedy, as well as sketch drawing, as means to thrive in his sobriety.

“Sketching calms my mind and gives me something to focus on,” he says. “Comedy fills me up with a lot of energy. Both mediums are like a puzzle. When something doesn’t look or sound right, they help my mind find the missing piece.”

Through his podcast, Don’t Take Bullsh*t from F*ckers, which he hosts with Greg Behrendt, Kane goes as far as helping others stay sober by directing them to resources and providing light-hearted wisdom through comedic flair.

But his story wasn’t always so hopeful.

Kane arrived in Los Angeles around 2014. The first year in California was harder than he’d expected, and soon enough drinking became a coping mechanism to endure stress and pain. Something he’s seen happen all too often among fellow performers.

That addiction and substance abuse are common in artistic circles is not exactly a mystery. Psychotherapist Matthew Bruhin says addiction tends to proliferate among artists because, while sensitive and full of ideas, artists are often introverted and prone to struggling in social settings.

“People think of performers as beautiful and creative,” Bruhin says. “They think the person they see on stage is the same person they see off stage. But on stage, performers are often putting on an act, and, once that’s done, they return to a state of insecurity.”

To deal with the pain and insecurity, Bruhin says, artists often resort to substance abuse.

Dr. Gordon, on the other hand, thinks addiction is not tied to any particular profession or even personality.

“It’s not the bad things that happen to you,” Dr. Gordon says. “But the great things that don’t happen [during a person’s formative years] that lead to abuse.”

Kane’s drinking worsened after someone broke his jaw during an argument. By that point, he says, his then-girlfriend had had enough. His friends were telling him what a bad drunk he was, and comedy wasn’t panning out the way he had hoped. But he hadn’t gotten his wake-up call yet. A conversation with a comic from Chicago, who was also trying to get sober, gave him the push he needed; a 12-step-program did the rest.

Kane never stopped doing comedy, not even during his first days of sobriety, despite the nervousness that pervaded his stone-cold sober mind every time he set foot into a club. Incidentally, his friends were all about his sobriety journey.

“You are not a good drinker,” they would tell him. To which he’d reply, “Then, why did you invite me out to drink?”

“Well,” they’d say. “You are the only one who wants to drink as much as me.”

Blurry memories of past karaoke nights with a beginning but no end in sight cross my mind.

While Brooke—who also participated in a 12-step program when first getting sober—says they don't feel the need to attend meetings anymore, Kane still benefits from them. With anxiety kicking in, he has found the community helpful.

“I was trying to get known in San Diego,” he says. “And my anxiety came back. I am just prone to it, but I never realized it before. When those emotions hit…that’s when relapses can happen.”

To avoid relapsing, Kane also keeps his circle small and packed with friends who are fully supportive of his sobriety, which he wears “as a badge of honor” on and off stage.

“What about those who insist on offering you a drink after shows?” I ask him.

“They are simply out,” he answers with no hesitation.

Thank you.

What are you doing these days?