Give them a reason to come back

Food industry workers are not rushing back to work, and it’s not just a money issue

Last week, the San Diego Union Tribune published a story about how hard it is for some local restaurant owners to find employees. TL;DR: It’s really difficult! So dire is the situation that Civico owner Dario Gallo is quoted as saying “It’s like a war” in reference to how cutthroat the competition to find willing workers is, which... I mean, okay. I’m no business owner, but I assume finding someone to serve fancy food is just a little different than getting shot at.

By no means is the U-T story unique: Just a day prior, NPR ran a similar piece about restaurateurs in Massachusetts struggling with the same thing. In both stories, business owners pontificate on the reasons for this labor shortfall, and while there are many factors—including career changes and lingering COVID trepidation.

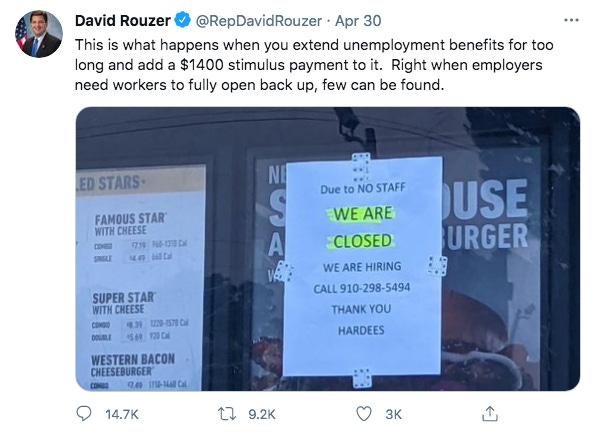

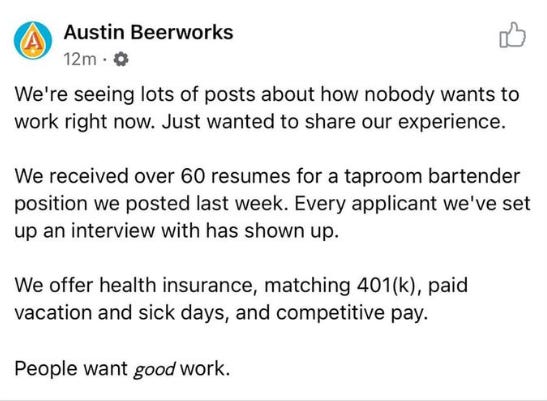

And if you’ve spent any amount of time on social media lately, I’m sure you’ve seen photos of restaurants posting passive-aggressive signs bemoaning the workers’ unwillingness to work.

The signs, the articles, the social media posts—it all paints a picture of the poor business owner. Nobody’s considering the business owners! [Helen Lovejoy voice] Won’t someone think of the business owners!?

I’m not here to shit struggling business owners—I honestly feel for the small businesses who’ve suffered or had to close down during the pandemic. But as much as we love to hear about business owners’ struggles and successes (i.e. the narrative of the American Dream), that’s only one side of the story.

The money’s not worth the burnout

If you see one of those “no one wants to work” posts from a struggling business, just scroll through the responses, and it’s inevitable that someone will unearth the business’ pay rate. It’s usually not pretty.

But Dario Gallo, the Civico owner quoted in the U-T article, offers $17 an hour for a host position. That’s nothing to sneeze at. Is it a liveable wage in San Diego? Probably not, but it’s a good amount above California’s $13 minimum wage, and way above the $9.50-ish range that’s often brought up in this conversation. Still, no one’s biting. Why is that?

It’s a symptom of capitalism where befuddled restaurant owners throw their hands up in frustration and wonder why anyone would refuse $17 an hour, but it’s not really as much of a conundrum as owners and press make it out to be.

It really should be no surprise that the food industry is fraught with abuse, exploitation, and other unpleasantness. Thanks to California’s multiple lockdowns, industry workers have had time to reassess their situations—which feels a little like a collective epiphany. Many workers, eager to abandon harsh working conditions, have walked away from the restaurant industry for good.

Lauren Mapp worked in bars and restaurants for 14 years before becoming a full-time reporter for the San Diego Union-Tribune. She’s grateful for her restaurant experience, and although the money could be good, it often wasn’t. It certainly wasn’t a sustainable income for anyone planning to buy a home in San Diego.

“I was working as a hostess and I was working double shifts every single day. I was working six or seven days a week, double shifts almost every day and I still couldn't keep up with my bills,” Mapp said during a phone interview. “For someone to be at a restaurant for, you know, 40-plus hours a week and still not be able to pay their bills...You shouldn't have to kill yourself at a job to be able to pay for your house.”

Krista Moores, a server/bartender of 12 years, said goodbye to the restaurant industry after returning to work during the brief period between California’s two lockdown orders.

“They called me on a Friday. They were like, ‘We're reopening on Tuesday. Can you come Monday? Oh, and we also got this brand new software. So we'll be retraining everyone on this new system,’” Moores said. “So I come back, and I'm expecting to see a lot of familiar faces. There was only six of us that came back out of at least 20.”

Despite the money, the high demands and modified environment proved too much for a seasoned veteran like Moore.

“For the first three weeks, it was absolutely miserable.” she said. “We were all working like eight to 10 hour days. We were making a lot of money, but I would have easily chosen to make less money and not burn myself out completely.”

There’s a quote in the NPR story from Jason Brissett—a kitchen worker who came from Jamaica on an H-2B visa to work at the Pilot House restaurant in Sandwich, Mass—that sums up the attitude that restaurant workers have to have these days, and I can’t help but die a little inside every time I read it:

"We can pull down maybe like 80 hours [a] week. It's really difficult. You don't want to overwork. You still want to go home back to your family and not die on the line," he says with a laugh.

With a laugh.

Ha ha.

****

“My job tried to bribe us with two weeks of back pay if we came back, then took it out of those people’s saved up vacation instead of the $5 million they got in PPP. The only reason I went back for a week last May was because I got a formal letter stating I was officially refusing work and implicitly threatening to notify EDD if I stayed on unemployment. This whole narrative that people are choosing to stay on unemployment when they’re being offered jobs is just BS. You can’t legally get benefits if you’ve been offered work. So I’m sure some people are lying to edd, but many are just doing side gigs and moving in with their parents.” - Brandee Bilotta, industry worker of 10 years (via direct message)

****

Rampant abuse from all sides

I have to admit, there’s something slightly satisfying in a Monkey Paw-ish sort of way to see eager eaters who’ve spent months wishing for everything to “get back to normal” who are now suddenly forced to endure a different dining-out experience than what they expected.

Regardless of my schadenfreude, however, the abuse that industry workers suffer from customers, management and coworkers is no joke. If hell is other people, then there are few hells more hellier than working in a bar or restaurant.

Although Lauren Mapp left the industry before the pandemic hit, she can’t imagine why anyone would go back right now, especially when confronting a rabid public who are now dining out after a year of being cooped up.

“I think that there's something to be said about the kind of person who feels entitled to go out to a restaurant during a pandemic,” Mapp said. “You have people who are coming into the restaurants, and they're expecting the same level of service they had 14 months ago. It's not going to be the same right now. Restaurants are short-staffed and everybody's a little bit afraid after being stuck at home for so long.

Former bartender Sage Beasley echoed Mapp’s sentiment.

“I think right as the pandemic took hold, customers were already increasingly hostile, and I think as the year went on, [their] behavior just became worse,” Beasley said.

Former industry worker Brandee Bilotta also described a hostile encounter that proved to be her final straw.

“The first night we reopened last May, I had a literal panic attack at work because our very first customer was rude to me when I asked him to wear a mask and sanitize at the host station. I completed my shift but I never went back.”

Other industry workers cited the exhausting need to be always “on” as a reason they left—a service that’s tantamount to providing unpaid emotional labor. Katie Reams, a former server of 20 years, likened the job to an abusive relationship.

“No matter what you have to smile. No matter what you have to try to make the customer happy,” Reams said. “There's so much emotional abuse that goes on in restaurants from guests and also management....Always acquiesce, always deescalate, never show your emotions, always make excuses.”

Reams said the general public’s lack of respect for the profession and patronizing superiority often made for toxic encounters with customers.

“I got asked, ‘so what do you really do?’ all the time. And always by old white dudes who were about to sign the credit card slip, so you know they're deciding what to tip me.”

But even more insidious than asshole customers is the rampant sexual harassment and abuse that’s embedded in the industry. It’s so prevalent that every woman I spoke with had experienced it on some level.

“I was sexually harassed on a regular basis by customers, and I was expected to just grin and smile and serve them a drink.” Mapp said. “Think of like the creepiest thing that someone could say to a young, 20 year-old girl, and I've heard it. That's a huge issue. This whole mentality of the customer is always right—well, sometimes the customer's a creep. But sometimes that customer is a regular and they're best friends with the owner, and you can't get rid of them.”

****

“I experienced sexual harassment at my job. It was just never really handled properly...[management] said ‘We’re going to make sure that you guys don't work any shifts together. We're gonna handle this in house.’ But they didn't let him go. They did an investigation. They brought in their in-house lawyer. They confirmed everything and then asked me whether I wanted him fired or not, which I thought was just really inappropriate to put that decision on me” - Krista Moores, industry worker of 12 years

****

What can be done?

As many people before me have pointed out, the current trend of industry workers leaving the profession feels like a sort of labor movement, a collective strike against the unfair and abusive practices that run rampant throughout the food industry. Rather than throwing more money at the problem—as is the case with the restaurateurs quoted in the Union-Tribune story—now’s a good time for big businesses to reassess their business model. For example, Gallo’s “war” quote from the U-T article encapsulates just how expendable big companies regard the people who work for them.

Dottie DeVille, co-owner of Til-Two Club in City Heights, says that many large corporations are stuck in a hands-off, hierarchical, and exploitative model that makes workers feel undervalued.

“We had the bar for 11 months before we were shut down. We were there every night, just saying hi to people or doing something, you know? So this is normal for us,” DeVille said over the phone. “But the people who have been doing this for years, they've all backed off. They've let their staff just run [the restaurants]. I think they're very out of touch with what's really happening with their employees. Now, you have to be out there. You have to be thanking people for showing up.”

DeVille laughed at the description of the beleaguered Civico owner calling his brother in to be a dishwasher, as depicted in the U-T story.

“What was the owner doing? Was he the chef? I'm like, you guys have to fucking get down and dirty and show up to your places, you know? It's disappointing.”

In addition to major attitude changes from management, the restaurant industry is in serious need of benefits and protections. Both Katie Reams and Lauren Mapp told me that they had insurance later in their restaurant careers, but also confirmed that those are still rare for restaurant positions. Firmer policies against against sexual harassment and enforceable consequences would go a long way, as well. And just the ability to just call in sick without guilt would be huge.

“There was a lot of pressure to make sure you came into work if you were sick, because if you couldn't get your shifts covered, you had to come into work,” Mapp said.

But as important it is for managers and owners to change their attitudes, it’s just as important for us, the general public, to change our mentality of what it means to work in the hospitality industry. We must stop thinking of these positions as “unskilled labor” and start regarding them with the same seriousness as any other career. It’s tough work, these workers deserve all the benefits, protections and dignity we associate with other professions.

“I think a lot of restaurant owners kind of see certain positions at restaurants as kind of starter jobs,” Mapp said. “And I feel like you should make every job something that somebody can potentially want to do for the rest of their lives.”

Big thanks to Jackie Bryant for helping with this story.

WEEKLY GOODS

Listen to this

Do you feel like you’re languishing? I feel like I’m languishing. It feels like I’ve been floating through the past week--not depressed (I mean, not more than usual!) but not exactly excited about anything. I didn’t realize how blah I was feeling until I saw this incredibly batshit video by Satanic Planet, and it felt like a psycho balm on my numb soul. The song is a wild ride of tribal drums chant-screaming (courtesy of Locust singer Justin Pearson) that’s truly invigorating and just a little scary. The video is equally manic, featuring Space Ghost animation, blasphemy, violence and subversive messages. I definitely needed this right now.

Read this

I didn’t watch Elon Musk host SNL last weekend. To put it politely: I do not care for that man. But I still woke up the next day feeling angry that we live in a society where so many are infatuated with a guy just because he’s rich, and he owns a company that makes things that appeal to our inner 6-year-olds. And driving around that Sunday, I had the vague desire to run every Tesla I saw off the road. But reading this thread about why Tesla’s are bad cars is just as good (and way less psycho!)

Think about this

Last week, I had a tweet that became slightly popular. Not viral, but maybe, like, ill? I don’t know. Anyway, I started thinking about a specific red, plastic cup and tweeted about it. The responses were great, and sent me down a warm slide of nostalgia. I hope it does that to you, too.

Got a tip or wanna say hi? Email me at ryancraigbradford@gmail.com, or follow me on Twitter @theryanbradford. And if you like what you’ve just read, please hit that little heart icon at the end of the post.

Julia Dixon Evans edited this post. Thanks, Julia. Go follow her on Twitter.

I was a server and bartender for eight years, and I definitely agree the industry is plagued with sexual harassment and transgressions on most labor protections. However, I think I'd challenge the idea that this is "skilled" labor. By definition, those are roles that require some higher education. There's nothing too terribly complex about listening to order, plugging them in a POS, and delivering food and drinks. Yes, sure, if businesses can't hire staff, they should raise wages. But trust me, as a small business reporter, I have literally seen the balance sheets of many small restaurants and coffee shops. They're not making the big bucks off the backs of their staff. Their margins are tiny. If they pay the workers more, we will surely pay more in menu prices to make up for it. That's not just something business owners say. It's a reality. But like you say, customers are chomping at the bit to eat out at restaurants. They'll probably pay the higher price without concern. But, you know, heyyyy inflation. People ignored this as a crazy right-wing claim, and yet the BLS is reporting the largest jump in monthly inflation this week since 1982.

EXCELLENT WORK <3