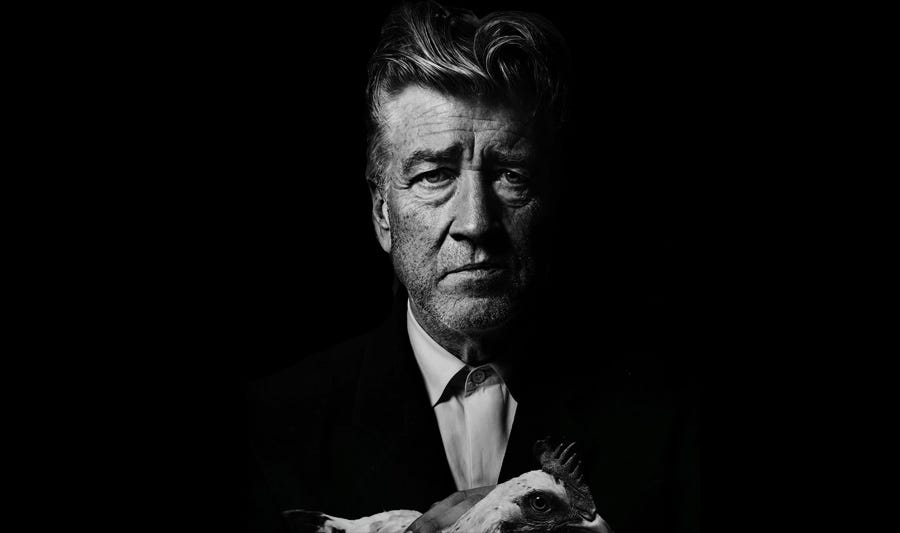

Five things David Lynch did better than anyone else

A tribute to one to my biggest artistic inspirations

I don’t often feel the need to comment on celebrity deaths, but David Lynch has been a huge inspiration on me since my dad let me watch Blue Velvet at the young age of 12. His death wasn’t surprising, but it still hits hard.

1. Reality

David Lynch has his own entry in the Oxford English Dictionary:

Lynchian: juxtaposing surreal or sinister elements with mundane, everyday environments, and for using compelling visual images to emphasize a dreamlike quality of mystery or menace.

“Surreal” and “dreamlike” are the words that people tend to associate with David Lynch, which... duh. But I’d argue it was through these aforementioned juxtapositions and the environments that captured real life better than any other director. Narratives, by their very nature, follow a prescribed trajectory—it’s what we come to expect. When films break free from the expected arc, we start throwing around words like “surreal”. But real life is not a clean, cinematic narrative; there are digressions, there are unknowns, there’s minutiae, there’s dislogic. If we could predict the plot of our lives, no one would want to live.

I remember watching Mulholland Drive at a local film night in my town’s library (props to Park City Film Series) when I was in 11th grade with a group of friends, and the experience shook me. I had never seen anything like it. I didn’t understand it. But I was obsessed. Why was there that frightening scene at the diner in the middle of the film, which is seemingly unrelated to anything else in the movie? Did the two lead actresses switch bodies? Who the hell was the cowboy?

But in the end, it doesn’t really matter. I still don’t really know what the movie’s about—maybe something to do with memory? And speaking of memory, after the Mulholland Drive screening, we went to Wendy's to talk about the film. I even remember my order: Frosty, fries, and 5-piece nugs. Or was it a soda, Junior Bacon Cheeseburger, and fries? Wait. Did we go to McDonalds?

That is to say, memory, like in Lynch movies, is unreliable.

David Lynch has famously refused to explain his movies, but he often indicated that he himself doesn’t really know exactly what they’re about, nor does he care—and I think that’s a valid (and incredible) artistic point of view. It’s like impressionism. We see what’s reflected at us, and it’s often what we know. And in that sense, Lynch was able to reflect our own fears, loves, anxieties, and joys better than any other filmmaker. And if that’s not reality, I don’t know what is.

2. Morals

David Lynch was never afraid to show the repugnant side of human nature. Sexual assault, violence and grotesquerie run rampant through his films. Roger Ebert—a very smart person— famously hated Blue Velvet for degrading Isabella Rossellini.

But I believe Lynch was wild a moralist at heart, and he was obsessed with the idea of good vs. evil. Beneath his dream logic and convoluted stories, there was always a moralistic battle being waged. There’s no shortage of evil in Lynch’s work, epitomized Blue Velvet’s Frank Booth, Dark Cooper and Wild At Heart’s Bobby Peru—characters that are so heinous that they make me nervous anytime they appear on screen.

While Lynch often explored the underbelly of American life, he was equally infatuated by the goodness that existed on top. His protagonists might as well have been peeled out of 1950s cops-n-robbers dramas. Agent Cooper is a shining example of All-American idealism. Despite his rampant anxieties, Eraserhead’s Henry Spencer tries to be a loving father. Films like The Straight Story and Elephant Man overflow with compassion for their subjects. And Twin Peaks: The Return is the most epic portrayal of good vs. evil since Stephen King’s The Stand. For many, it was frustrating to see Agent Cooper trapped in the body of subvocal Dougie Jones for the majority of The Return, but Dougie is Lynch’s most pure creation—a force that improves the lives of everyone he encounters. Dougie is Lynch’s way of saying, no matter how much evil exists in the world, there’s still profound goodness.

3. Horror

I watch a lot of horror, but no director has scared me as much as David Lynch. Whether it’s the pale man’s phone call with Bill Pullman in Lost Highway, Bob’s slow-motion running toward the camera in Twin Peaks, the “got a light” sequence in The Return, or Laura Dern’s grimace in Inland Empire, there’s one scene in nearly every Lynch film that I wish I hadn’t seen.

The success behind these indelible horrors is Lynch’s understanding of nightmares and his documented perfectionism for sound design. He was a classic filmmaker in the sense that he deliberated over how sound paired with images, and could create harmony or dread—especially dread—without really showing anything. He also knew how to contrast, juxtapose, and light an image to render it uncanny.

The effect is that even scenes that use basic horror techniques feel novel in Lynch’s hands. He knew that moving a character from the background to foreground (Bob in Twin Peaks, Laura Dern in Inland Empire) is terrifying.

He knew that characters looking at the audience is terrifying.

Lynch also knew that randomness, digressions, unexplainable blips in our expectations are fucking terrifying. Of the many memorable scares in Blue Velvet [and spoiler alert if you haven’t seen it], the one that always gets me is near the end when Jeffrey enters Dorothy’s apartment and finds two corpses: Dorthy’s husband and the man in yellow. As he’s assessing the scene, the man in yellow, who died standing up, suddenly flicks his arm and knocks over a lamp. Is he actually dead? Or is it just a physiological reaction to death? Lynch doesn’t dwell; he barely even acknowledges it. The story moves on, but we’re still shaking.

And let’s not forget his most famous jump-scare: the diner scene in Mulholland Drive (please watch it if you haven’t). It’s an amazing scene in that the characters tell you exactly what’s going to happen, and then it does, but you still scream.

4. Knowing what the audience needed, not what they wanted

David Lynch did not pander. He knew what stories he wanted to tell, and we’re all better off for him.

Critics hated Fire Walk With Me; it was even booed by the audience at Cannes. No one knew how to feel when Laura Palmer didn’t turn out to be the golden child whose death upended the world for two seasons. She did drugs, had sex, endured a harrowing and abusive homelife. It was not what the audience wanted, and perhaps the initial hatred for this subversion was that Lynch revealed our collective fetishism and valorization of dead, beautiful white girls.

Lynch subverted expectations again with The Return. Those excited for Agent Cooper’s valiant return were instead treated to 15 hours or so of Dougie Jones doing slapstick. But like I said, The Return wouldn’t have worked without a shining beacon of light as pure as Dougie to counteract the sheer evil of Dark Coop and the Black Lodge. As it was airing, my social media feeds were stacked with people infuriated with Dougie Jones, but I get it: some people just want familiarity, and it’s a good thing we have comic book movies for them.

5. Artistic integrity

David Lynch is best known for his films, but he was also a painter, musician and songwriter. He treated art seriously. He also didn’t let anyone compromise his visions. And despite his reported Midwestern kindness and gentleness, he did not tolerate people trying to water him down.

There are many memes and clips that showcase Lynch’s steadfast relationship with art, but my favorite is this one where talks about watching movies on your phone.

I also really like this clip of David Lynch getting mad at a producer for suggesting he cut a scene down (“Who gives a fucking shit how long a scene is?”).

This is all to say that in a cultural landscape that has turned art into content, and everyone’s just vying for attention, artists like David Lynch are few and far between. Art that he produced wasn’t merely consumed—it inspired.

This is great, Ryan!

Today my mom apologized to me for letting me see the Elephant Man when I was four. I was like, "No way, thank you!"